|

|

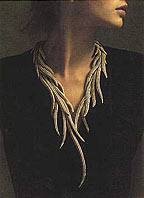

Fig.1. "Paeonia Byzantina"

from the "Golden Peonies" collection, necklace in 18

carat gold.

MARAMENOS& PATERAS JEWELLERS.

|

Fig. 2. "Ear of Wheat", brooch in

22 carat gold. Copy of a 3rd century BC find from near Syracuse.

CHRISTOTECHNIKI S. TOMAZINAKIS & SONS

|

|

Fig. 3&4. Classic

traditional pieces, mainly handmade in 18 carat gold and set with

diamonds and pearls.

NIK. G. KANDARAKIS

|

|

Fig. 5. Handmade brooch, in 18

carat gold, with handcarved onyx cameo of pegasus embellished with

tiny diaminds.

|

Fig. 6. Byzantine

style cross, symbol of religion, symbol of power. 18 carat gold set

with rubies, emeralds and pearls

LAVORO, MARIA N. POULKOURA-VOUTIRA

|

Athens quickly grew into a major metropolis where craftsmen gathered from all

over Greece. The constant need for ecclesiastical vessels kept alive the

traditional minor art of silver- and goldsmithing, while the observance of

certain mores and customs, such as presenting a gold cross at the christening,

the exchange of jewellery on betrothal, sustained many silver- and goldsmithing

workshops throughout Greece, where objects were wrought in age-old techniques.

In Crete for example, it is customary for the prospective groom to present his

bride-to-be with a necklace with `boutonia' at the engage- ment ceremony. The

design and technique of the filigree decoration on the delicate gold `boutonia'

-beads hark back to Minoan times.

There is no doubt that the purchasing pub- lic's preference for European

jewellery led to a lull in some of the traditional techniques. However, many

were still applied in the minor arts, as well in isolated workshops in old

silver- and goldsmithing centres such as Ioannina, Corfu, Rhodes, Macedonia and

Stemnitsa in the Peloponnese. The supply of raw materials during the nineteenth

and the early twentieth century was almost exclusively from Constantinople

(Istanbul), which continued to be one of the most famous silver- and

goldsmithing centers. In parallel it was a usual phenomenon for workshops to

melt down old jewellery to make new pieces, according to the customer's wishes.

This meant that many notable old ornaments were irrevocably lost.

From about 1930 onwards the new craftsmen working in the Athenian goldsmithing

workshops created beautiful handmade jewellery in the European style using

traditional techniques. So even though craftsmen had ceased producing

traditional jewellery as such they were proficient in the techniques.This fact,

combined with their experience and talent, enabled them to meet the new demand

for Greek jewellery particularly copies of ancient Greek ornaments, mainly from

tourists, that began in the 1950s. In response to the needs of this new market

Greek jewellers not only applied traditional techniques but also renewed them by

exploiting the achievements of modern technology as well.

Despite the prevailing adoration of everything European during this first.

period, counter forces emerged, mainly from enlightened intellectuals who, in

their endeavor lo arouse the bourgeoisie from the lethargy of imitation into

which it had fallen, delved ever deeper into those elements composing the

enduring unity and cohesion of the Greek spirit. We cite indicatively General

Makryyannis and his `Memoirs', the painter and 1821 freedom-fighter Vryzakis,

the poet Angelos Sikelianos, the writer Pantelis Yannopoulos, the painters

Parthenis and Kontoglou, as well as many other important personalities who

sought out the essence of Hellenism and the components of its creative course

and continuity. Their efforts bore fruit. later, constituting the substratum of

the modern cultural floruit. and the revival of interest in the values of recent

Greek civilization. Jewellery was included in the creative course of Greek art

that. soon developed, evoking wider interest at home and abroad.

|

|

|

Greece jewellery pages Copyright ©

by Add

Information Systems. (Greece)

|

|

|